Making Him Proud

My father was not a man who expressed his emotions. Well, that’s not completely true - he could, and did at times, express anger quite emphatically. Sometimes I understood why, sometimes I did not. I learned early on that it was best not to argue or question.

It was affection

that he really did not express. I

honestly can’t remember a hug or even a pat on the back. It was the way he was; likely the way he was

raised. His genealogy was German. He was born in 1918 as WWI was drawing to a

close. He lived through the Great

Depression as a child. There were surely

hardships, but I don’t know what they may have been because he never talked

with me about them. But, clearly it was

an era where there was less emphasis on education and much emphasis on hard work.

He had several jobs in his youth and as he and my

mother set out raising their own family. The longest he worked at any one employer was his

job at one of the local paper mills. It

was a time where you were expected to work your way up. He started working the pulp wood piles, a

fairly dangerous job that required climbing the stacked logs in all kinds of

weather and, using a picaroon, to steer logs into the machine that peeled the

bark off, and then into the “chipper” that more or less chewed the logs into

small pieces, so the wood could be cooked down into pulp and eventually be made

into paper.

Like many men in this area of Wisconsin, my dad worked

at the mill most of his life. It was a

job that I heard he resisted taking in the first place. It was good-paying, steady work, and therein,

lied the problem. I think he knew that,

once in the mill, he wasn’t coming back out until he was old. It was one of life’s paradoxes that steady

work felt at the same time to be a relief from financial worry and a trap for

the soul. If he dreamed of being

something else, he never shared it with me, but I suspect that he did.

In the nearly 30 years of his career in the mill, he progressed

from the wood pile to a department superintendent. But, he also witnessed the beginning of the

end of that kind of career path. During

his time, he saw the work world transforming from management teams that worked

their way to the top, to more and more management teams consisting of college-educated

and younger men who started their careers already half way up the ladder. Maybe that had some influence on our

relationship.

I didn’t intend to be different than my father, but it

turned out that way. I was the last of

seven siblings. My oldest brother Jim

was the only one who attended college after high school. His first round of higher education was cut short by the

Navy. My brother Mike took welding

classes at the Tech College. That was

good because it was about real work.

I had fairly good grades all through grade school and I

liked learning. By the time I went to

high school there was no discussion, but I knew that my parents, especially my mother,

expected that I would attend a four-year college. I didn’t question it either; I looked forward

to it. Looking back now, I think my

father was uneasy about my college attendance because he may have felt a bit

left behind, since he only had a high school diploma. I know that I never thought about it that

way, but I think he may have. To make

matters worse, although I thought briefly about a degree in chemistry, in the end I

chose to pursue a degree in English. My

heart was set on being a writer. I know

that my father didn’t know how to relate to that. To make matters even worse, I

developed a love of poetry and hoped to somehow fashion that into gainful

employment. I know my father really didn’t

understand that.

It also didn’t help matters that during my college

years that my mother, who had already dealt once with cancer, began another battle

with cancer that would eventually take her life. My father grew quieter, more tense and was

drinking more heavily than ever. My

mother passed away on Christmas Eve, 1979; four days after I earned my diploma

from St. Norbert College.

As the youngest, I was the final child left at

home. To say that our relationship

became tense at that point would be an understatement. I was able to get several poems published,

but I also discovered the hard reality of being a poet. First, there were (and are) few publications

that accept poetry. Second, and more

important, when you get something accepted, the “payment” is usually several

free copies of the publication. It is

hard to put bread on the table with a box of free publications.

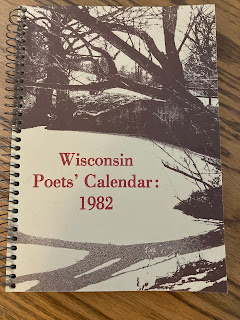

I only shared one of my free publications with my

father. A poem of mine was accepted and published

in the Wisconsin Poets' Calendar: 1982.

He took it from me and set it on the end table by his recliner without opening it up to

my poem, and changed the subject. All

was not lost; at least he might use it as a calendar I thought.

My father passed away from a sudden heart attack two

years later, in April of 1984. When my

siblings and I started cleaning out the house for sale, my sister Sandy called

me to my parents’ bedroom. “Dan, I think

you’d want this,” she said. I went to

the bedroom and there on the nightstand, on my father’s side of the bed, was the Wisconsin

Poet’s Calendar: 1982. It was opened to

the second week of July – the page my poem appeared on. It was the first time that he ever told me

that he was proud of me.

His Peace,

Deacon Dan

Comments

Post a Comment